BOVINE TB - A POLITICAL DISEASE

To many on the outside, farming is envisaged as the ideal lifestyle. One of being out in our beautiful countryside, doing what for many of us is our passion, working alongside our stock and nature. Sometimes its tough, and it feels like nature and the weather is doing everything possible to beat you. Cold and dry springs not allowing crops to establish or thrive and reach their potential, or sometimes deluges of rain that can destroy crops or saturate land making it impossible to work on.

Meanwhile in the farmyards there will inevitably be that one animal that will somehow interrupt your routine, whether it escapes from its pen or field, or a cow that doesn't seem to be getting on with calving herself and will require some assistance. It goes without saying that this always seems to happen on that evening that you'd organised to go out. I've lost count of the number of times my long suffering wife has been dressed up and ready to leave the house when I have to make that call and say "sorry, hopefully it shouldn't take too long and we can still make it". I think it's taken as a given now though that that actually means sorry, maybe next time.

Would I change it? Never, and in all honesty, I don't believe my wife or family would either. For every negative, there's a hundred positives. We are so blessed to be able to bring up a family in these surroundings and into this way of life. To be able to have a true understanding of food and where it comes from. Many people question how, as a farmer I am able to feel love and become attached to an animal, but then send it to slaughter and go on to eat that animal. For me, the answer is a simple one. It's all about respect. That animal was bought into this world and lived its life for a purpose. Throughout its life I have cared for it, ensured its had everything that it has needed, and kept it safe and hopefully happy. Once it has matured and ready, I am then happy for that animal to leave the farm and fulfil its purpose.

Occasionally you will lose an animal through ill health or injury. As I always remember my dad saying, when you have livestock, you will inevitably have deadstock. On those occasions that we do lose an animal for whatever reason, then that does upset me. Not because of any financial loss, but purely on the basis that the animal didn't live its full life and didn't fulfil its purpose. It's as if it was a meaningless life. That's life though, and something we have to be prepared for and something that we deal with. What I don't think I'd ever be able to truly deal with though when we lose an animal for no obvious reason. When an animal appears to be fully healthy, but tests show there's a possibility of it carrying a disease. This is the reality facing farmers across the country though. This is the reality of Bovine TB.

The process begins around 8 weeks prior to testing. The letter arrives from animal health to notify you that your TB test is due. For me personally, that is an every 6 month occurrence. It’s something that's always in the back of your head, but once that letter arrives, the stomach starts to churn and the nerves set in. As the weeks go by and the date gets closer, the nerves intensify and the sleepless nights begin. The days immediately before testing, tensions can be high.

With up to 800 animals to test, it has become a 4 day job for us, needing at least 6 of us plus the vet who does the testing. Every animal over 6 weeks of age has to be walked into a handling system where the vet can safely handle the animal and check it. Its identification number is taken and cross referenced with the list that the vet has to ensure that every single animal is tested. The vet will then clip the hair from 2 parts of the cow’s neck to identify the test sites. At each site the skin is pinched between a set of callipers with the thickness of each site recorded, and then the cow is injected at each site. The upper of the 2 sites will be an Avian strain of TB. This is used as a control to differentiate between reactions to the actual Bovine TB infection and just a reaction to the bacteria which can be commonly found within the environment. The lower of the 2 sites is the specific Bovine TB strain. It's then a 3 day waiting game.

It sounds a simple enough task, but the reality is far from simple. The whole ethos of farming cattle is to keep them as calm and stress free as possible. To allow them to do as they wish as much as we can. Suddenly we are having to round them up into holding pens, then forcing them through a handling system where they'll be trapped and handled. It goes without saying that they are going to be spooked and scared. This is where we aim to have as many staff as we can muster together and plan the system in such a way that the animals are naturally funnelled into the handling system with as little herding and stress as possible. There are still animals that will try to escape, running through you or trying to jump over gates or barging forward and trampling each other. No matter how hard you try or how well you plan, there's always that chance of injury to man or animal. In the last 2 years, as well as for the usual cuts and bruises, we have had one helper knocked down and end up in A&E with concussion, and one animal try to run through the gate of the handling system, breaking its neck on impact. Nothing is natural about what we are doing and so as a result you are always working with a degree of fear in your head.

After 2 days of testing and a day off to resume the normal farming work, it’s time to start all over again. Every animal has to go through the whole system again. This time though all that needs to be done is for the animal to be identified and the skin at the 2 test sites to be measured again, recorded and checked against the initial results. If the lower test, the Bovine TB, site has a lump greater than the upper test site, Avian TB, then the animal is considered to be a reactor. Regardless of age, condition or anything, that animal is then condemned to be slaughtered, and the whole farm is placed on lockdown, meaning that the only animals that are able to leave are those heading directly to be slaughtered. The farm will remain in lockdown like this until it has had 2 TB tests, 60 days apart, that have all come back as being clear. For some, those in the worst affected areas, this is ongoing for years with no realistic end in sight. Susie and her family are one of many farmers trapped in that never ending cycle.

"We are a third generation pedigree dairy farm based on the Wales, Shropshire border. We have been shut down with TB for the last five years. TB is now part of daily life on our farm. Every 90 days we complete an array of skin and blood tests. These tests are not only stressful for our cattle but are gruelling days physically and emotionally for all those involved. It demands a full family effort. This team composes of my 71 year old father in law, workman, myself and my husband plus grandparents to care for our children. The cows find the testing increasingly stressful and nervously anticipate the process. One of the biggest and frustrating challenges is lost time and the associated labour costs involved in the process from start to finish every 90 days.

Not just the testing day but the moving of cattle, repeat tests, valuing the animals, loading the animals for slaughter and the extensive paperwork requirements. Despite the intensity and spectrum of testing we have lost 260 animals in the last 5 years, it is truly heart-breaking. These range from heifers to milking cows and all must be replaced to continue to be a viable farm. It is absolutely soul destroying watching your some of your best cows being loaded and taken for slaughter and losing not only the cow but sometimes the entire genetic line.

We pride ourselves on caring for our cows, working hard to improve conditions, calf units, processes and strive for the best genetics but none of this makes any difference. We have sat at the kitchen table many an evening discussing TB and I believe the hardest part of this battle is that it feels unbeatable. We can’t beat it, we can’t fight it and we can’t vaccinate against it. I believe I’m speaking for lots of farmers in our area by saying we feel our hands are tied by government legislation and policies. We are in a silent but demoralizing battle. Will this be won in my lifetime?"

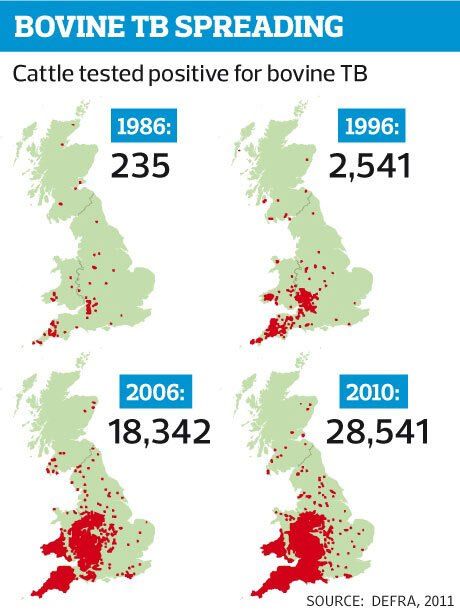

Since 1950 the government have had a bovine TB eradication program in place to stop the spread of the disease in our national herds and reduce the spread into the wildlife pool as well as for the risk of spill over into other species. While there are still very few cases of Bovine TB in cats and dogs, it is on the increase in other animals, particularly alpacas. There is also a very low risk of humans contracting it, less than 1% of all TB cases, via drinking unpasteurised milk from infected cows, or exposure to bacteria from excretions, particularly via an open wound. By the late 50’s the government incorrectly believed that it had won the battle with Bovine TB, but small pockets were still appearing around the SW of England. In 1973 the badger was given protected status, and since then their numbers have recovered and latterly boomed. In that same period cases of Bovine TB have followed that same trend.

The governments disease control strategy has become somewhat of a hot potato in recent years with the badger culls in targeted hot spots dividing many opinions. Many have accused intensive farming and the large numbers of cattle within a close proximity as the cause for large numbers of reactors and campaigned to stop the culls to protect the "innocent badgers" as they see it. The result of this public outcry has only divided opinion more and turning Bovine TB into a political campaigning tool. Bovine TB has become a political disease.

Science and studies over decades have shown the increasingly strong links between badgers and bovine TB. Testing has shown that TB has its own unique strains in localised areas, and those same strains are found within the badger population of those areas. Furthermore, independent testing of badgers within the hot spot areas have shown Bovine TB rates to be as high as 40%. Without the culling of badgers in these areas of high infection we would be doing the national badger population, and the whole wildlife pool a great disservice. Regular testing of our cattle will identify infection and the animal can be culled to prevent further spread of infection as well as for maintaining the welfare practices by not allowing infection to take hold and causing suffering to that animal. Without control within the badger population and the whole wildlife system what is going to prevent spread of disease, and what will protect the clean, disease free areas? Are we really prepared to stand by knowing that so much of our wildlife is becoming infected and suffering such a slow and debilitating death?

Many of those who oppose the cull are calling for vaccination of our cattle. I think this is something that the majority of farmers, certainly those I know, would be in favour of, but it is only one part of a complete toolbox that we need to both control and eradicate this awful disease. There's no point in bolting the stable door once the horse has gone. We need to get it back inside and then bolt the door! Vaccination will only be a success where disease levels are low and haven't already taken hold.

To successfully get on top of this situation we need to take back control in the hot spot areas. The culling trials have shown that it can be done and incidence levels in those cull areas have dropped significantly. If we could only work together, by getting an approved vaccine passed for use and using it in the areas that are disease free or low risk alongside culling where it is endemic, hopefully we will be able to regain control.

As a dairy and beef farmer I want to take control of Bovine TB. I want to protect my herd from the stress of testing and the threat of culling. I want to protect my business from the financial implications of TB. What I also want though, is to be able to protect the Badger, the deer, Muntjac and the rest of our wildlife from this awful and debilitating disease. To stop the risk of the disease spilling over into other species as it takes a greater hold, and the threat to the whole ecosystem. To protect our beautiful English countryside and all those who inhabit it.